Back on the beat: Quest program helps Meridian policeman return to the job he loves following a brain injury

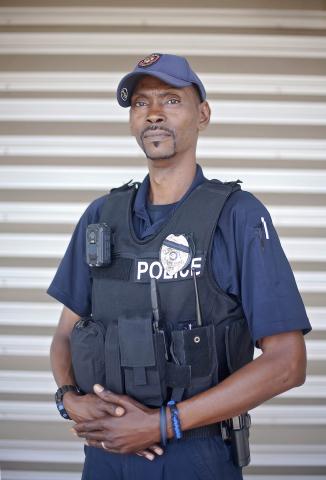

As a 20-year veteran of law enforcement, Devie Freeman is used to closing cases.

But still open is the case of what exactly happened to him on the night of Aug. 22, 2016 at his Canton, Miss., residence.

“In the wee hours of the morning, around 3 a.m., apparently I was attempting to go downstairs—I’m assuming to get a bottle of water—and I fell down the stairs,” Freeman said. “Later, I was informed that my door was open and my alarm went off, so the police came to the apartment for the alarm call and they found me laying on the sofa and bleeding.”

Freeman was airlifted to the University of Mississippi Medical Center, where doctors removed two pieces of his skull to relieve the pressure on his brain. He was put into an induced coma and was placed on a breathing machine, spending 19 days in the ICU. In all, he spent two months in acute care at UMMC, before being discharged to inpatient rehab at Methodist Rehabilitation Center on Oct. 23, 2016.

“It was a very, very long recovery,” said his wife Atlene.

Freeman, a 47-year-old father of four, doesn’t recall his accident, or much of his time at UMMC and MRC. That’s quite common for those who suffer a traumatic brain injury, as he did in his fall.

What isn’t so common, though, is that Freeman is now back to his former beat as the liaison officer for the Meridian, Miss., Housing Authority, less than a year after his accident.

“I’ve worked with a number of patients from law enforcement,” said Clea Evans, Ph.D. “Some of them went back to a modified job—they just went and did desk work. I’ve seen a lot get back to that level. But it’s difficult for them to get back to active duty, being out in the field and carrying weapons.”

As head of the neuropsychology department at MRC, Evans evaluates patients to determine their cognitive ability and recommends further treatment or, if possible, a return to work.

“Part of our job is to find out what this guy does, and to find out if he has the skills to go back and do it safely,” Evans said. “With someone in his position, there is a lot more on the line.”

Evans says that professions like doctors, nurses and law enforcement are often the most difficult to return to work following a traumatic injury. Police work requires a high level of function for activities like driving, firing a weapon and critical thinking and decision-making.

“I saw social skills as a very important element of his job—being able to talk to people, to think quickly and problem solve on his feet, and being able to negotiate and de-escalate situations with people in conflict,” Evans said.

Freeman was referred to Quest, Methodist Rehabilitation Center’s comprehensive outpatient program for people with brain or spinal injuries who wish to make a successful return to work, school or home life. Quest’s team of clinicians includes physical, occupational and speech therapists certified to assess a patient’s level of function after injury. They also work closely with Evans and the neuropsychology department.

“We initially tested Devie in December,” Evans said. “We felt like he still had some difficulties in focused areas. We used that as a guide to tell them at Quest what he most needed to work on. He actually had a lot of normal range scores at that time, so some areas had improved.”

While Freeman was an inpatient at Methodist Rehab, he was still experiencing the confusion, memory and attention problems, and difficulty with speech that are symptoms of a brain injury. While he says his recollection of his time in inpatient rehab is hazy, he knows he was motivated by the support of family, coworkers and friends.

“I know my mother-in-law told me I should get better so I could come home and eat dinner,” Freeman said. “That was a motivation to me. I can’t remember exact conversations, but I do remember people coming to see me.”

Freeman’s godmother, a former school administrator, also kept him on task.

“Whatever she said is what I ended up doing,” Freeman said. “She just has this look that motivates you.”

Driven by the support, with the guidance of his therapists and a dogged determination to get out of the wheelchair he was using, Freeman began to emerge from his fog.

“The therapists really work with you to help you stay on track,” he said. “I knew each time what progress I needed to make so I just kept on moving with it. Then it was like I did a complete 180.”

But just as his mental health had begun to recover, it was discovered that Freeman had suffered some unseen physical trauma in the accident, a left clavicle fracture.

“They were focused on getting him right in the head, but until he could talk and let them know he how was hurting during physical therapy, they just didn’t know,” Atlene said.

That was one of the challenges he faced when he came to Quest, says Patricia Oyarce, who served as his physical therapist and primary caregiver at the outpatient program.

“Overall he came in testing well physically,” Oyarce said. “So we worked on general endurance and conditioning. His main problem was he was left handed, and that was the side he had his injury on.”

“Being a lefty, I couldn’t imagine not using my left hand,” Freeman said. “So if she asked me to do this or that, I made sure to do one step above it.”

But first, Oyarce said, she had to address Freeman’s issues with postural hypotension. It occurs when a person’s blood pressure drops abnormally when going from a lying or sitting to standing position, and is common after a brain injury.

“We started working on addressing that, by doing progressive activities and changing positions while monitoring his blood pressure,” Oyarce said. “Then we were really able to move forward with more high-level activities.”

With getting Freeman back to work in mind, Oyarce devised therapies to help strengthen the muscles he would be using out in the field.

“In his case, his vest can get very heavy because he carries a lot of gear in it,” Oyarce said. “He brought his vest to Quest so he could work out with it. Because of his left shoulder he couldn’t wear it long at first. So I did things like have him walk on the treadmill wearing his vest.

“We also had to work on his balance, so it was interesting that I had him doing some of the same tests that he used to test people for drunk driving.”

Freeman also saw occupational therapist Kari Richeson, who worked with him on other on-the-job tasks.

“We had to work on his functional endurance to make sure he could tolerate a full day of work,” she said. “He also needed to drive again, so we focused on reaction speed and visual processing.”

Quest’s speech therapist and staff psychologist both cleared him right away, as he was not having any difficulties with speech or emotional issues.

“We all see the person from a different perspective according to our scope of practice and we contribute to his return-to-work letter,” Richeson said. “That is a letter that I write, that is contributed to by PT, OT and neuropsych and signed by the physician. I then make myself available to both employee and employer for any work site visits, were the patient to need any accommodations or the employer to need any education or assistance.”

By March, Freeman was ready to be reevaluated by Evans to determine if he could go back to work.

“He had already been looking at a plausible plan to return to work,” Evans said. “We reevaluated him, and I felt like he had improved enough to handle the cognitive aspects of his job, so I recommended to his employer that he then undergo weapons recertification.”

Richeson says they often rely on the employers to assess the areas that PT and OT are not equipped to do.

“I could help him with his endurance, but I couldn’t exactly say he was proficient at shooting,” she said. “Luckily, we have the support of the law enforcement agencies, who can clear them for the things like firing a weapon and driving a patrol car. We allow the employers to use the standardized tests they already have.”

Freeman passed his recertification and returned to work in March.

“When I first started back, I had to ride with my partner because that was the process I had to go through,” Freeman said. “After I completed the driving rehab course at MRC and passed my driving test, I can now drive on my own.”

“I would say his pace was remarkable,” Richeson said. “He had a really great recovery. It’s always what you hope for, but it’s not always an option to put somebody back in such a high-risk role like a police officer.”

Atlene says she never imagined anything like this happening to her husband. For the wives of police officers, there’s always the thought of something happening to their spouse on the job.

“From the day he first started, it was always in the back of my mind,” she said. “But police work is his passion, so I couldn’t stop him. For such a freak thing to happen was unbelievable.”

Freeman says his wife’s tireless support carried him through his recovery.

“From the moment they called my wife to let her know what had happened to me, she was there,” Freeman said. “I may not have seen it—I don’t remember it, but from day one she was there. All my family and friends will attest to it. And she’s still right there for me.”

“Another key to his recovery was his attitude,” Richeson said. “He came in every single day 100 percent willing to do what we asked him to do. We almost hated to discharge him because he was an inspiration to us and our other patients. He was the exact kind of guy you would want out policing our streets.”