You’ve just stumbled upon a man lying unconscious in the woods. He appears to have fallen from a tree stand. What do you do?

That question confronted participants of a recent Wilderness Medicine Seminar at Methodist Rehabilitation Center’s Flowood campus. And the answer was probably a surprise to some.

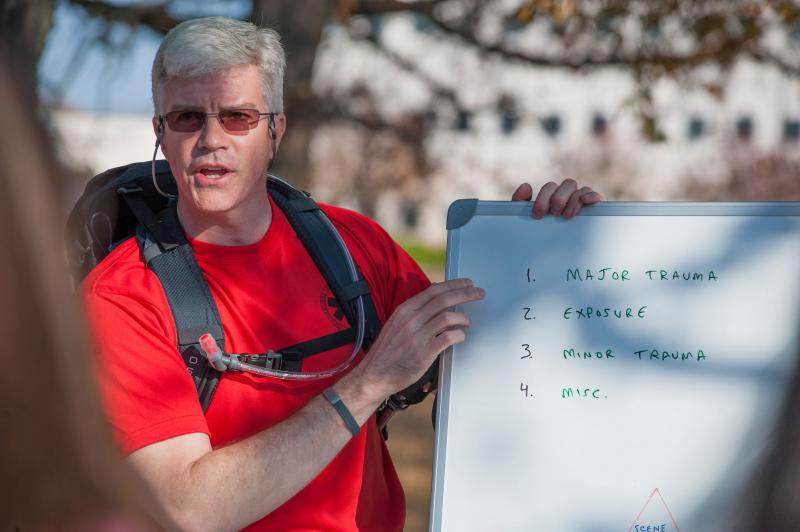

Rather than rushing to act, it’s best to size up the scene for threats to your own safety, advised seminar leader Dr. Philip Blount.

“No. 1, you don’t put yourself at risk,” said Blount, a board-certified physical medicine and rehabilitation physician at Methodist Pain and Spine in Flowood, a division of MRC. “That may sound selfish, but the worst thing that can happen is for one victim to turn into two victims.”

An enthusiastic outdoorsman, Blount has been involved with the Outward Bound program and was previously certified as a Wilderness First Responder by the National Outdoor Leadership School. He became interested in teaching wilderness medicine as a 2006 faculty member at the University of Mississippi School of Medicine in Jackson. And it wasn’t long before he was sharing his knowledge during hands-on training trips to places like the Pearl and Okatoma Rivers.

“I knew my students would eat this up,” Blount said. “It’s an opportunity for students to have a break from their studies and have fun learning. It’s a 2-for-1.”

Wilderness medicine focuses on techniques to assess injuries, stabilize conditions and provide basic life support in remote settings. And given Mississippi’s rural nature, it’s a skill set that benefits more than just physicians-to-be.

That’s why Hannah Miller, the latest president of UMMC’s Wilderness Medicine Student Interest Group, made sure other UMMC health care majors could take advantage of Blount’s expertise. “My goal was to include other groups like nursing,” she said.

In all, nearly 40 students gathered for the recent Sunday seminar. And this time the destination was closer to home. The acreage outside MRC’s Flowood clinics was the setting for learning stations for major trauma, minor trauma, exposure injuries and wilderness readiness.

The tree stand scenario represented major trauma. And Blount tapped medical student and emergency medical technician R.J. Case to lead the session. “This is a great way to take what is learned in medical school and apply it to real-life situations out in the woods,” Case said.

As he evaluated pretend victim/fellow med student Hunter Dulaney, Case was mindful of Blount’s recommendations. He began by assessing risks to his safety and making sure there wasn’t more than one injured person on site.

Since Dulaney was feigning unconsciousness, Case asked a partner to dial 911. “If they’re not responsive, the first thing you do is call for help,” Case said. “Then you’re looking for immediate life threats.”

Blount’s “triage triangle” calls for rescuers to assess the victim’s airway, breathing, circulation, disabilities and environment and follow up with a head-to-toe exam, a check of vital signs and a thorough medical history.

Case said it’s also vital to investigate how the victim might have been hurt. Since a tree stand fall likely caused Dulaney’s injuries, Case demonstrated the proper way to handle a suspected spinal cord injury.

At the minor trauma station, medical students Austin Southern and Rosario Guastella played the part of bike wreck victims as session leaders Cody Pannell and Lauren O’Malley demonstrated proper ankle taping and leg splinting techniques.

For a session on exposure injuries, medical student Jordan Jackson posed as a duck hunter who had fallen into the water on a 15-degree day.

To forestall hypothetical hypothermia, session leader and medical student Jonathan Redding wrapped Jackson “like a burrito” in several layers of insulation—never mind that it was nearly 70 degrees that Sunday.

Fortunately for Jackson, he wasn’t asked to portray a heat stroke victim. Redding said the remedy for that would be an immediate immersion in ice water. “Every minute spent over 105 degrees is a bit more nervous system damage,” Redding said. “The goal is cooling to 101 degrees or lower.”

Redding said heat stroke is the No. 1 killer of young athletes. And Blount said it’s much easier to prevent heat illness than to treat it. He recommends wearing a hat, sunglasses, sunscreen and lip balm and drinking plenty of water.

“Hydration is the best solution for a number of these patients,” Blount said. So he typically carries 3 liters of water in a bladder in his backpack during wilderness outings.

As for what else to pack, Blount said the popular outdoor store REI has a good list of things to carry, including resources for navigation, hydration, sun protection, insulation and nutrition.

As for first aid kits, Blount said there is no one-size-fits-all suggestion. “You’re really looking at something specific to the event or activity you’re going to be doing,” he said.

And it needs to be accessible at all times. “You should keep them with you,” he stressed. “If you are ready, you are the stud. But if you’re not ready, you’re the turkey.”

“Doctors are expected to know what to do in emergency situations out in the world,” Case said. “So it’s good to be prepared for what might happen.”

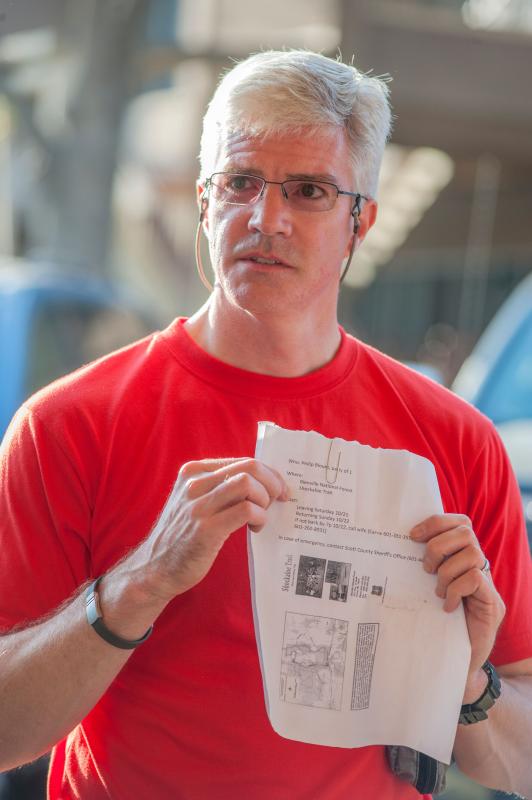

And that includes acknowledging you might be the one needing rescue, Blount said. “For every outing, you need to leave a note with two people you trust that says where you’ll be going, what you’ll be doing, what time you expect to return and what authorities to call if you’re not back by the designated time.”