It’s not how Gray Spencer expected to spend his 22nd birthday—heading home to New Albany after three weeks at Methodist Rehabilitation Center in Jackson.

But on April 22, he was just happy to have overcome a traumatic brain injury in the middle of a pandemic.

“I’m just really thankful,” Spencer said. “I’m blessed to have had good therapists. Without them, I definitely wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Right now, he’s on a trajectory to return to college and his job as manager for the Ole Miss basketball team.

But neither outcome seemed likely a little over a month ago. On March 16, Spencer was driving to campus when he lost control of his car and crashed into a tree along Highway 30.

“We got a call that scares you to death,” said his dad, Bob Spencer. “They said your son is being airlifted, and he’s on a ventilator.”

At North Mississippi Medical Center in Tupelo, doctors discovered bleeding inside Spencer’s brain. “They said he had such a blow, his brain had probably hit against his skull,” his dad said.

The doctors decided against surgery, believing the bleed would resolve itself. But Spencer was hardly out of the woods. He remembers nothing of his two weeks in Tupelo or his arrival at Methodist Rehab on March 31.

“The first day, he was sitting in the wheelchair, and he couldn’t even lift his head up. It was down in his lap,” said Methodist Rehab physical therapist Kollin Cannon.

“He had a really flexed posture,” said Methodist Rehab occupational therapist Chuck Crenshaw. “He was bent over in a ball, and I couldn’t even get his back extended with the assistance of two other people.”

Spencer also couldn’t communicate. “For three days, he couldn’t get any words out,” Cannon said.

So his initial therapy centered on promoting alertness, verbalization and following commands.

Four days in, it was as if he suddenly woke up.

“He started doing sit-ups on the tilt table,” marveled Cannon. “I asked him how he felt and he said: ‘Elite.’”

That was a Saturday, and by Monday he was trying to walk. “His balance was terrible, but he was cracking jokes,” Cannon said.

“They were like: Who is this guy?” his dad said.

A former high school basketball standout and cross-country runner, Spencer was a regular at the gym.

“I worked out and lifted weights every day,” he said.

“He was about as conditioned as our players, for sure,” said Ole Miss basketball Coach Kermit Davis. “And he has great grit, I’ve seen that from him working with us.”

His therapists saw it, too.

“He had such a strong base of strength to work with that he was able to muscle through some things that would have been difficult for other people,” Crenshaw said. “He kept making jumps and was always pushing. He kept getting better so fast.”

“The first week until now has been a complete 180 degrees,” Cannon said. “That’s pretty awesome to see.”

An Ole Miss fan, Crenshaw knew from Twitter chatter that Spencer might be coming to Methodist Rehab. And he was hoping he’d be one of his patients.

Initially, the Spencers had considered a transfer to an out-of-state rehab hospital. But news that it would take 10 days to be admitted made them reconsider the choice.

“A neurologist in Tupelo said that one rehab that is as good as any is Methodist in Jackson,” said Bob Spencer. “And I have a niece that works at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, and she said good things about it, too. It also turned out he could get in quicker. I think God led us here.

“I can’t say enough about the people—from the cleaning staff, the nurses, assistants, doctors and therapists—everybody who had a hand in it made us feel they were more than happy to help.”

Methodist Rehab’s caregivers include physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses and respiratory, physical, occupational and speech therapists who work as a team to help patients achieve their goals.

And their extensive experience with brain injury patients makes them masters at keeping people motivated in the therapy gym.

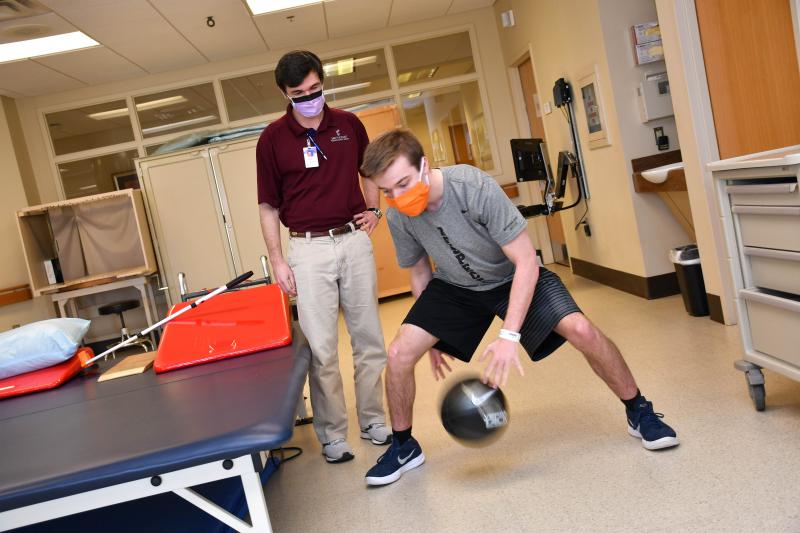

In Spencer’s case, that meant incorporating his love for basketball into exercises to improve his strength, endurance, coordination and balance.

“We worked on shooting free throws to improve his high level depth perception and coordination,” Crenshaw said. And to work on his weak left side, Spencer caught firm bounce passes in his left hand while balancing on an unstable surface.

With Cannon, Spencer also did a lot of pacing the halls. “The other day we walked 1,000 feet,” Cannon said.

Spencer deemed it “a PT record,” which is in keeping with his highly competitive nature.

So speech therapist Taylor Miller decided to use his love of one-upmanship to achieve some therapy goals. They went one-on-one during timed cognitive therapy tasks.

“I’m not going to lie, he did beat me on occasion,” she said. “He really did make great progress. There’s no reason he shouldn’t be able to continue with his education.”

Spencer said it helped that he had an outpouring of support. Since they couldn’t visit because of the COVID-19 crisis, Coach Davis and the team kept in touch via calls and texts.

“That has been motivating me to get back, and I am ready to get back,” Spencer said.

Coach Davis, in turn, is ready to put him back on duty.

“We’ll welcome him with open arms in any capacity he wants to be in,” Davis said

In the meantime, Spencer plans to enjoy being back home after more than a month away.

For weeks, he has been pining for Mexican food from Mia Pueblo and Cracker Barrel macaroni and cheese.

But he’s learned COVID-19 might interfere with his culinary wish list.

“I woke up and everything had changed,” he said. “I told someone where I wanted to eat when I got home, and they said no way it will be open. When they told me how bad it was, I didn’t believe it.”